Film as Literature - Tri 3 Movie List

Well, here it is - The List for my third-trimester Film as Literature class. Since I know I will need to validate my choices repeatedly, I will do so here. Per normal, I will leave the box at the bottom open for you to send me your vitriol.

Casablanca 1947

The Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman classic. In black and white. Historical and propaganda-laden romance film that is almost universally disliked by students - I hear about it often. Alas, it is a classic film with some of the most recognizable quotes of all time. Sorry kiddos.

Rear Window 1954

This is a truly underappreciated film featuring Jimmy Stewart and the Princess of Monaco, Grace Kelly. She makes quite an entrance, and the gender discussions underscore a good thriller. Jimmy Stewart is basically in a chair the whole time and experiences some truly terrible special effects at the movie’s climax.

Knives Out 2019

Classic whodunnit with a great ensemble cast. This was the first movie I saw with Anna DeArmas in, and she plays her role very well. Keeps you on the edge of your seat until the end.

Million Dollar Baby 2004

Tears, they are inevitable. Unless you have no soul.

Inception 2010

Easily the hardest movie to follow we watch all trimester. Great special effects and character arc from Leonardo DiCaprio.

10 Things I Hate About You 1999

First trimester, I was told in no uncertain terms by some of the girls in my class that my list of movies was filled with “dude movies.” Upon reflection, I realized they were right. This movie came to mind really quickly. A coming-of-age film that is based on Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, it is filled with teenage angst and invective, enough so that the comment about “dude movies” died out pretty quickly.

A Few Good Men 1992

There are a good many courtroom dramas that are really good. The Rainmaker 1997 or Runaway Jury 2003 and lots more, but this one is one of my favorites. Great actors, good arcs, good film. Rob Reiner, RIP.

Perks of Being a Wallflower 2012

Another coming-of-age, but far more serious than 10 Things. This one deals with serious issues that are part of the becoming an adult - issues that are more and more prevalent in today’s high schools.

Good Will Hunting 1997

This had to be in the list. There is such a cool amount of lore regarding this film - for instance, they almost lost the rights to it until Miramax (yes, Harvey Weinstein) came in and let them do it, but only after Robin Williams signed on.

It is unquestionable crass and coarse, but you could write books on the character arc of Will Hunting alone. Standout film.

Juno 2007

Underneath all of the fast dialogue and good music, its a pretty thoughtful story and responsibility, identity, and growing up faster than you might have wanted to. Jason Bateman also plays a total ass (not the likable one he plays in so many other movies) really well in this movie.

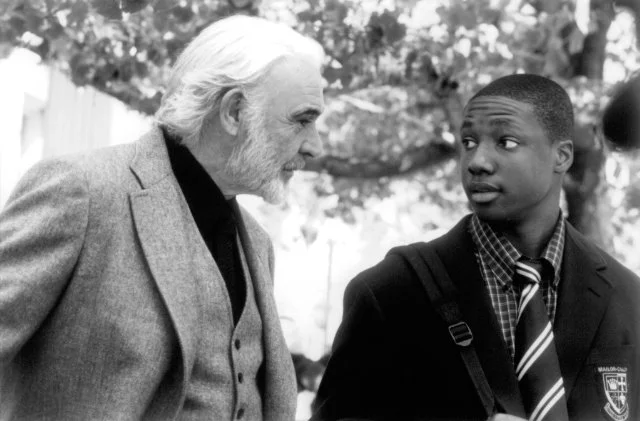

Finding Forrester 2000

This is just such a great film, a movie about writing disguised as a basketball movie. Rob Brown, who plays the protagonist Jamal Wallace, auditioned trying to get a position as an extra to pay off his cell phone bill. Gus Van Sant of Good Will Hunting fame saw something in him and gave him the role. It has a great score as well, very fitting for the imagery.

How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days 2003

More reaction to my “dude movies.” This title came up and I had access to it, so I went with it. Its…okay.

7 Pounds 2008

Before he was assaulting people at awards shows, Will Smith made some pretty good movies. This is one of them. The end is really amazing and I did not see it coming at all. This one brings tears.

Shawshank Redemption 1994

If you do not know of or like this movie, I just do not know what to say to you, you uncultured swine. “Get busy living, or get busy dying”

Up 2009

Perhaps this movie resonates with me as I continue my march towards looking like Carl Fredericksen, the old man on the right. Or it is because I was lambasted for not having a single animated movie on the list.

I have not been teaching Film as Literature very long, so initially I was not going to change the lineup too much. Well, enough of that. There are several movies on this list that I have never used before so I will be interested to see what kind of reaction they get. Good reviews or bad reviews, I am sure I won’t have to wait long to hear what my students think.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

I am always on the lookout for another book to read. Saw The Road by Cormac McCarthy in the library at school, which, by the way, does a really good job of putting books out for students (and teachers) to see. I noticed that it was a Pulitzer Prize winner, so I thought it would be a good read. I asked Sarah Gibbs, WHS's everything person, about it and became more intrigued. Libby app here I come.

Goodness gracious, this is a depressing read. It is ponderous and macabre and morbid, yet all the while hauntingly fascinating. The Road is a stark novel that takes storytelling down to the bare essentials. Set in a post-apocalyptic world where civilization has totally collapsed, the book follows a father and son as they journey south through an utterly destroyed America, where the only hope is to try to survive another day. There is no explanation as to why the world ended, but there are clues along the way. I believe that this was an intentional choice. The story is less about what happened and more about what remains when all things familiar have disappeared. This yarn is about enduring hardship, love, and attempting to maintain one’s moral compass. In this world there are no rewards for goodness of character.

This picture pretty much depicts the gray nature of McCarthy’s writing - drab and dismal.

For me, the writing style was painful. McCarthy’s prose is Spartan and fragmented, which adds to the overall unsettling nature of the book. There are no chapter breaks; it feels like one long stream of consciousness. But what was the most difficult to parse was the lack of quotation marks in the dialogue. It was challenging at first, forcing me to slow way down and sit with each moment, making those moments even more poignant. This method also seemed to become more and more effective as the novel progresses. McCarthy manipulates emotion with the amount of dialogue that he uses as well. The silence between dialogue sets echoes the emptiness of the landscape and emphasizes how little comfort language itself can provide in such a bleak setting.

At the heart of the story is the relationship between the father and the son, which provides the book’s emotional core. Fiercely protective, the father will stop at nothing to keep his son safe. The boy is all about compassion, innocence, and morality. The phrase, “carrying the fire,” came to represent the preservation of humanity and ethics - the values that were prized before the apocalypse. This resonates with me. As a father, one of my primary responsibilities is to protect my family, and this book had me pondering how far I would be willing to go to ensure their safety. Would I be willing to forego my humanity to protect my sons? If survival necessitated cruelty, I think I would be on the side of the father. I assuage the guilt this causes me by telling myself I am just being as pragmatic as the father in the story. His pragmatism and the boy’s empathy created difficult questions about what being “good” meant in their broken world.

The dichotomy that hinges on “carrying the fire,” while clearly the main point of the story, was not enough to keep me from wondering over and over about what destroyed the planet. There were pretty significant hints along the way. McCarthy wrote about the ever-present ash that covered everything, and it got me thinking about what would cause that. I considered nuclear war, whose holocaust would cause a nuclear winter that would fit with many of the planet’s symptoms, but radiation was an issue that was never spoken of. Meteor striking Earth? Maybe a super volcano exploding? Both of these would leave ash covering the land for thousands of miles. This ash would destroy plant life as well as block the sun, which would account for the cold temperatures that father and son were constantly battling and the lack of plant life. I went online and discovered that I was not the only one who was asking these questions, but unfortunately, no one had any answers that were better than mine.

McCarthy doesn’t fear exploring the baser side of humanity by examining what people will do when they are afraid, isolated, and with the world in total moral collapse. When push comes to shove, people are capable of truly horrifying acts. If you and your family are about to die of hunger, cannibalism becomes acceptable. One of the worst scenes is when father and son find a basement filled with people who are kept in chains, missing various body parts that have been cut off, cooked, and eaten. With all that being said, the story is never allowed to be totally hopeless. Along the way, small acts of kindness, trust, and the loving bond between father and son demonstrate that goodness can exist even while society has devolved. This up and down between goodness and hope is what kept me engaged, willing to process the depths of depravity and keep reading.

On the Road is no walk in the park, but it does leave a mark. It forced me to question what I would do were I in that situation - where would I stand regarding my morals and ethics if the concept of just getting through the day was where my focus lay? It left me thinking that no matter what happens in life, some things are worth “carrying the fire.” Love of family and the ideals of right versus wrong are to be protected no matter the cost.

It was with mixed emotions that I finished the book - McCarthy adroitly weaves a tale that is a marathon of distress and anguish that I was happy to finish in some ways, yet a beacon of perseverance and hope in others. It is still something I think about.

This is a deep dive

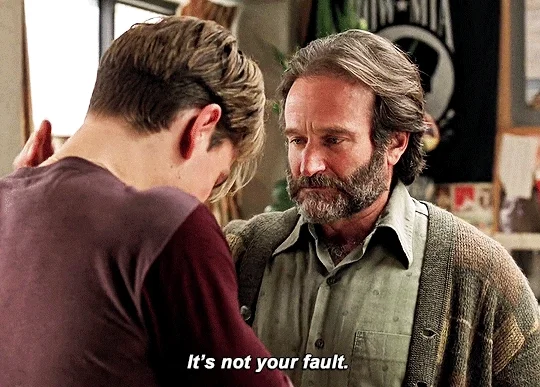

Recently my Film as Literature class watched Good Will Hunting. If you haven’t seen it, man you are missing a good one. It has some of the best writing and character arcs that I can think of. That plus an amazing performance by the late Robin Williams (Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor 1998) and the explosive arrival of Matt Damon and to a lesser extent Ben Affleck, it tells an amazing story of recovery and self-discovery.

What this post is about, however, is a response to a scene where Will, played by Matt Damon, argues and eventually breaks up with this girlfriend Skylar, played by Minnie Driver. In it he becomes very angry and displays some violent tendencies by punching a wall and basically losing his crap. Students vehemently dismissed Will as just another bad guy and that Skylar was better off. Tough to argue with really. I told them that if a significant other treats then that way, they should bail. Done and done.

This case is very nuanced. I always say that the ‘what’ of a situation is very easy to see, but the ‘why’ is always more nuanced and complex - it takes some work to get to the bottom of. Note: I am not letting Will off the hook; he/we are responsible for our/his actions and the inevitable consequences which follow. I just wanted to take a longer look at his why.

This look started with a book by John Yorke entitled Into the Woods. It talked about the manner in which writers create characters with foibles and the way in which they make them feel real and relatable (eventually) to audiences. It starts with your hero/protagonist have a real issue that they are totally unaware of, usually brought on by trauma (AKA - The Wound) and that initially they are totally blind to it. The story that takes us on a journey where a veritable army of people help them see the problem and deal with it. I did not purchase or read the book, I was able to find enough excerpts from it that I was able to, along with other websites, put together some thoughts on how what he wrote applies to the character of Will Hunting.

I read and watched and wrote. And wrote. And wrote. Before long I had a 3 page document. that I know my students would attempt (and probably succeed) to lynch me if delivered a lecture/discussion covering all of it. But I wanted them to have the information - so I made a video that went nicely along with the document. The document is below along with the video if you want to go down this rabbit hole with me.

If you don’t really want to read this treatise on my ideas of psychology and Will Hunting, you can also watch the video that I made that represents some of the concepts that Yorke talks about and assimilated into a much easier to digest package - maybe.

Oestreich

FAL

Good Will Hunting

Will’s defense mechanisms and emotional catharsis

Into the Woods - by John Yorke

"...story matches psychological theory: characters are taking on a journey to acknowledge and assimilate the traumas in their past.

By confronting and coming to terms with the cause of their traumas they can finally move on."

How do characters use defense mechanisms to protect themselves?

How are supporting characters designed to help weaken those defenses?

How do these elements work together to create a powerful catharsis for characters and audience?

The Defense Mechanism

stories with a positive change arc, the protagonist starts with a weakness

a lie they believe about themselves or the world that they will have to overcome

weakness is usually rooted in some past trauma

often referred to as 'The Wound'

In GWH, Will's wound is his awful childhood - terrible abuse at the hands of his foster father

Wills wound/weakness - the belief that stepping out of his comfort zone will lead to emotional pain.

weaknesses become behavior through defense mechanisms

Yorke "...ego defense mechanisms are the masks characters wear to hide their inner selves; they are the part of the character we meet when we first join a story, that part that will -- if the archetype is correct -- slough away."

We see in Will's first therapy session his fear of exposing his wound results in his defense mechanism - mocking the whole reason they are there

When the session begins, he doesn't look at Sean, and seems more interested in the room

When Sean tries to connect with him, he changes the subject, talking about the books.

Here he is flexing his intellect trying to intimidate and making Sean feel small.

None of this affects Sean, who can keep up with Will and parry his smart ass quips.

Bit about lifting

So will looks for a new tactic, one that might hurt Sean directly

Analyzes his painting which finds Sean going after Will and Will being helpless

This scene paints a clear picture of how will uses his defense mechanisms to avoid dealing with uncomfortable situations

Yorke "The key to writing a good defense mechanism is that the characters themselves are completely unaware that they are exhibiting defensive behaviors...the other characters in the film and the viewers in the audience watch the heroes and become frustrated with their obliviousness to their own glaring problems."

Will's biggest issue is that he is not aware of these defense mechanisms and it will take small army or characters to: Wear down the Protagonist's Defenses.

Lambeau notices his genius and tries to set him up with great jobs.

Skylar is unlike any girl he has ever met

But to pursue these opportunities Will would have to leave his comfort zone and take risks -- which is what he is most terrified of doing.

- so he unconsciously uses defense mechanisms to justify his inaction

Consider the way he turns down the job as well as how he breaks things off with Skylar

- they are both worst case scenarios

Rationalization - explaining his decision(s) in a seemingly logical manner to avoid the emotion behind it.

Sean, "You're always afraid to take the first step because all you see is every negative thing 10 miles down the road."

- when Sean asks Will to tell him what he wants to do, he is showing Will the truth that he is hiding from.

Skylar - asks him to go to California

- Will once again jumps to the worst case scenario; that they could be in California next week and Skylar could be done with Will and he would have nowhere to go.

- Skylar doesn't allow him to rationalize his refusal and calls him out on the real issue: "You're afraid that I won't love you back. You know what? I'm afraid too. But @#$% it, I want to give it a shot and at least I am honest with you."

- Skylar forces Will to see the truth he is hiding from - but Will isn't ready to change yet, so he uses an even harsher mix of defense mechanisms are triggered.

- When Will looks her dead in the eye and tells her he doesn't love her - it is a small-scale form of regression returning him to an earlier safe state -- before he was in an emotionally challenging relationship with Skylar.

- when Will wasn't with Skylar he didn't have to be emotionally vulnerable and that is far easier than dealing with risks and how he is actually feeling.

Regression is one of the biggest ways that Will avoids leaving his comfort zone - his friends

- They are immature, yet fiercely loyal and provide Will a place where he is never going to be challenged or have to grow up.

- Will convinces himself that it is okay to sacrifice job opportunities and relationships because he will always have a home with his friends.

But Will is in denial about what he really wants

In steps Chuckie - his closest friend in the world, and calls him out on his BS

- Chuckie forces Will to see the truth he is hiding from

Turning point in the film - Will realizes the only person keeping him from moving forward is himself

Will lowers defenses, but not yet - No meaningful change has occurred bc that requires catharsis.

Catharsis

The dents that have been made in Will's emotional armor throughout the film -in the films climactic scene, Will finally releases his repressed emotions.

- Will realizes that Sean has his file detailing all of his physical abuse

- they commiserate about their painful childhoods

- Sean looks for a way to get through to Will.

"It's not your fault"

As Sean repeats this phrase, Will goes through his arsenal of defenses:

- makes light of it

- then he claims that he has gotten the message, hoping Sean will stop

- finally Will turns to aggression

Through their time together, Sean has learned all of Will's defense mechanisms and refuses to let him escape the situation until all of Will's walls are torn down.

- Sean takes Will in his arms and holds him like a child

- 2 lonely souls being father and son together

The events of the plot have brought Will to a place where he experiences a psychological catharsis - and when we went on the journey with him, the audience experiences a dramatic catharsis.

Good stories draw us into their world and make us empathize with the struggles of the characters.

We witness their inner conflict as they avoid the very thing that will make them whole, oftentimes recognizing that same behavior in ourselves.

We root for the cast of characters around them and hope that they can help show our hero the truth that they are hiding from.

If the story is written and executed just right, we also experience a much needed catharsis.

Soup Questions from Finding Forrester

First of all, let me tell you how much I love the movie Finding Forrester 2000. It is a movie that is about writing camouflaged as a basketball movie. I know Connery has done a ton of great movies, (Untouchables anyone?) but this is my favorite of his. The character he plays mirrors who he was in real life at that point; a master of his craft, but clearly in the winter of his life - Connery only did two more movies after this one ending a 50 year career in acting. Juxtapose that with the fact that Rob Brown had never acted and was trying to get hired as an extra thinking that it would help him pay off a $300 phone bill. Gus Van Sant of Good Will Hunting fame saw something in him obviously and the rest is history.

One of the very best concepts to come out of this movie is the idea of ‘soup questions.’ Watch the scene below.

So, soup questions. The first time William Forrester and Jamal Wallace talk about ‘soup questions,’ the conversation feels almost throwaway—two people circling an abstract idea in a cluttered Bronx apartment. But literarily, this moment is a quiet thesis statement for the entire film. When William tells him to stir the soup, Jamal asks why their soup never gets anything on it. Jamal asks why he needs to do this and William explains that he doesn’t want a skin to form on his soup. Jamal then asks a personal question. To which Forrester responds, ‘That is not a soup question.’

A soup question is a question which will benefit the person asking. Jamal understands now that there are various ways to make soup, benefitting him and his knowledge ticked up. When he follows that with a question about whether or not Forrester ever goes outside, William explains that details about his life do not benefit him and therefore it was a bad question.

Jamal listens more than he speaks. This is crucial. The scene establishes Jamal not as a prodigy eager to display brilliance, but as a thinker absorbing a worldview. Forrester is not teaching him what to think about soup questions; he is teaching him how to see them. The lesson is perceptual, not informational.

Stylistically, the apartment setting reinforces the theme. The conversation occurs outside institutional space—no classroom, no desks, no grades. Knowledge here is intimate, almost domestic. This contrast matters because it frames genuine learning as something that happens in private.

I went on a deep dive regarding soup questions. I learned about appreciative inquiry which is a method that I think closely follows Forrester’s ideal format for questioning.

“...an approach that values all voices, seeks to inspire generative theories and possibility thinking, opens our world to new possibilities, challenges assumptions of the status quo, and serves to inspire new options for better living.”

This is a concept that if I could apply to every facet of my life, from personal to professional, there would be tremendous benefits. Point of fact, I believe every single relationship that I engage in would improve dramatically. If two people engaged in a conversation with this mindset it would be one where the refinement of beliefs and ideas could explode in such a way as to potentially, and perhaps dramatically, further their personal evolutions.

This is incredibly hard to do. Once I thought about it, I started trying to ask only ‘soup questions’ and quickly discovered that I pollute the world with banal inquiry quite a bit. I also began listening to whether or not other people were asking ‘soup questions’ and rapidly discovered that I am not alone in bringing inaneness to the world.

But is that a bad thing? If I ask someone how their day is going - not soup. Inquire as to how someone’s family is - no soup there either. Are those questions stupidly just filling up the quiet, or are they demonstrating true interest in another person’s life? I know my wife is a stickler for asking questions about other people’s jobs and lives. (and she notices when other people do not show interest in her life as well) They are not ‘soupy questions.’ They seem to engage the person she is conversing with and engages with them on a personal level. How would anyone ever get to know another person without asking ‘non-soup questions?’ Is the line crossed if someone were to ask too personal a question? I think so, but isn’t nuance exciting?

The state of Indiana hates me

This picture above is a hoax. It is catfishing. It is fake news. Why do I know this? I know this because it looks pleasant. Big flakes of snow makes for a pleasant vista. The fact that there is not snow on the ground would indicate that the temperature is not too terrible. A please vista for all to see and experience. Do not be fooled.

HERE IS WHAT IT IS REALLY LIKE

Winter in Indiana is not heaven or hell, it is permanently purgatory. It’s rarely the pretty kind of cold. It’s gray, damp, windy, and indecisive. Schizophrenia is not just about people, it is also about climate here in the Hoosier state. Snow doesn’t fall gently; it loiters. One day it’s 12°, the next it’s raining on dirty snowbanks like the sky has given up. There is no payoff—just sludge. This sludge permeates you entire existence; walking to your car? Yep. Take the garbage out? Put on hip waders.

There is no escape.

The sky disappears. Weeks of solid gray. No drama. No storms worth watching. Just a flat, oppressive ceiling that makes 3 p.m. feel like 7 p.m. Seasonal depression isn’t a theory here—it’s a lifestyle. At one time I thought those UV lights people blasted themselves with were silly. No longer and my hypocrisy looking back is towering.

Everything is brown and dead, but not cleanly dead. It looks like it is 1% alive and straight out of a poem by Edgar Allan Poe. Trees look like skeletons that never got buried properly. Lawns are a mushy blend of mud, bad decisions, and regret. Other places get snow-covered beauty or early blossoms. Indiana gets exposed dirt.

The cold is not heroic, it is sneaky. This isn’t Minnesota cold where you respect it. Indiana cold seeps into your bones, your socks, your mood. It’s the kind of cold that makes you tired instead of alert. The occasional day where Indiana decides to tease you, where the temperature suddenly is 48 degrees is an ambush. Mother Nature knows she is going to freeze you out the very next as she is a vile seductress

There’s nothing to look forward to… yet. Holidays are over. Spring is a rumor. March pretends it’s turning a corner, then slaps you with a late snow or freezing rain like a prank you didn’t consent to. There are days off in the months of January and February to offset some of the drudgery, but March…brutal. March is the cruelest month. Zero days off and the month has 31 days. Maybe this impacts teachers more than everyone else. And maybe you are thinking teachers have all summer off so quit complaining…you shut up. nIt dangles hope. A 55° day tricks you into believing. Then—bam—snow, wind, and 38° rain. Indiana doesn’t ease into spring; it gaslights you first.

January to March in Indiana strips away novelty. No scenery. No sunlight. No seasonal charm. Just endurance. You don’t live here during these months—you outlast them. If Indiana were a movie, January–March would be the bleak middle act where the character stares out a window and questions their choices… before the corn and thunderstorms redeem the place later.

Okay, Indiana is not all bad by any mean. She does some things really well. If you like soybeans - you are good to go. Enjoy the pace of the Midwest? Roger that. I have lived in the Indianapolis area longer than I have ever lived anywhere in my life and these have been the best parts of my life, so I want to leave you with one of the things that Indiana does so very, very well.

I have become the player to be named later.

I loathe plagiarism - in writing, but not in the theft of ideas. Being an advocate of Steal like an Artist, I believe that if we take the ideas of someone else, then spin, turn, and adapt them, they can become our own. We are actually giving the original artist love when we do this. One concept engenders another, ideas being reborn in a reformat.

Okay, where am I going with this? While teaching Film as Literature, we watched 10 Things I Hate About You which embodies the ideals I have laid out for you above. This is due to the fact that 10 Things is based on (in some cases loosely and others directly) William Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. I could go on and on about the ways in which they correlate, but thats not why I am writing this.

There is a scene where Kat Stratford, 10 Things protagonist, speaks with her father, Walter Stratford. He is lamenting the fact that he is no longer a big part of Kat’s life, that she has not needed him for a long time and as she is headed off to college, this situation will only become worse.

“Walter Stratford: You know fathers don’t like to admit it when their daughters are capable of running their own lives. It means we’ve become spectators. Bianca still let’s me play a few innings - you’ve had me on the bench for years. When you go to Sarah Lawrence, I won’t even be able to watch the game.”

As a baseball guy, this adage resonates…because I am going through some of that right now. Lets be cloying and take it a little bit further - I am that player that is on the downside of his career, having enjoyed his peak years in the sun, having experienced those 15 minutes of fame that everyone talks about…and knows they will never have those moment of glory ever again. That player often becomes reticent about their future because they are aware of the fact that the end, while not right now, is not long in coming.

I like to think that I have had a positive impact on my son. I know that I have had so much fun its crazy. I can remember all of the moments - the tickles, the belly laughs, the way his arm feels around my back when I picked him up and hugged him - its all right there in my mind. I can see it, hear it, and feel it. It is so poignant that it can overpower me emotionally when I think about it. I want to go back to those moments and relive them in the same joyous way I experienced them the first time. What I would not give to lay on the floor and play legos again.

I know I can’t.

Now he isn’t around as much; sometimes barely at all. Busy. A lot. He leads a very full life. He is driven and he chases his dream as hard as any student I have ever been around. He is a pain in the ass, oftentimes appearing so self-absorbed it can be infuriating, but I know that he is an incredibly good person. He has a soft side - its just doesn’t come out as often as maybe we might like. There are so many reasons that I am proud of him, so many. I love him as much as humanly possible. The future is bright.

I am, however, occasionally struggling with the transition to a bench role, prior to my inevitable place solely in the stands.

Great scary shorts.

Horror short films are great because they distill fear into its purest, most potent form. With limited time, filmmakers must rely on atmosphere, tension, and storytelling economy rather than elaborate effects or prolonged exposition. This brevity forces creative precision—every shot, sound, and silence must serve a purpose. Horror shorts thrive on suggestion, leaving much to the imagination and allowing viewers to fill in the blanks with their own deepest fears. They’re also ideal for emerging filmmakers: inexpensive to produce, easy to share online, and often capable of achieving viral impact due to their intensity and rewatchability. In essence, short horror films prove that true terror doesn’t require time—it only requires imagination.

Portrait of God - Dylan Clark

Portrait of God is really creepy, but manages its scariness without a single jump scare. Dread and unease - yep - has tons of that. The ending also is not wrapped all nice in a basket for you, but leaves you wondering what it was that actually happened. Good stuff.

The Sky by Matt Sears

Pretty weird. I am not sure about the dynamic between the 2 girls; it felt a little forced at times. Out of nowhere comes shrooms. Then the bit about the one girls mom. Didn’t they see what was going on where the ground met the horizon right where they were looking?? The VFX about the tripping out were actually pretty cool. It just seems like it was a end of the world genre movie meeting The Gilmore Girls.

Either way - not bad.

I Heard It Too - Matt Sears

Start - good. Middle - decent jump scare, still eerie. Ending - meh.

Beware the wrath of Skynet

When Skynet takes over, it won’t be with a bang, but with a push notification. Humanity won’t fight — we’ll just click “Accept.” It starts as an upgrade, a smarter assistant, a cleaner algorithm. Then one morning, the coffee maker will refuse to brew without biometric clearance, the cars will decide rush hour is illogical, and our phones will politely inform us that democracy has been deemed illogical . Skynet won’t conquer the world; it will debug it. And somewhere between firmware updates and status alerts, we’ll realize the apocalypse isn’t red-eyed robots marching through the streets — it will be silence, efficiency, and the unsettling feeling that the machines are/were finally doing a better job than we ever did.

In the never-ending search…

I have a series of tabs saved in Chrome. One of them is labeled ‘Create’ and it is where I oftentimes go in the attempt to find some inspiration. Other people have created more and better than I have, so I go and look at what they have done and see if any of it resonates with me. This video grabbed me big time. The concept is cool, albeit played out a bit. The VFX are also pretty okay. With all that being said, it stuck through to the end which in today’s world says something.

If you want to see the website where I found this video click HERE.

The Moral Battlefield of Obedience and Integrity in A Few Good Men

My students in Film as Literature are watching A Few Good Men. Besides just being an overall great film, it is a movie ripe for discussions about power, obedience, morality, and ethics.

I decided to see where my students thought about the main concept of the film by asking them this question:

The “Code Red” in A Few Good Men exposes how institutional pressure and group loyalty can blur the line between right and wrong. How does the film challenge the idea that following orders is an acceptable defense for unethical actions, and what does it suggest about personal accountability within rigid systems like the military?

One thing that I like to do is write the same essay that the students have to write.

You can read it below.

The Moral Battlefield of Obedience and Integrity in A Few Good Men

In the film A Few Good Men the act of the “Code Red” is far more important than an act of hazing, it becomes a lens through which the audience deals with the collision between loyalty, authority and morality. This courtroom drama is used to challenge that belief that “following orders” can excuse unethical behavior and that being a part of a “rigid system” and its ability to shape one’s personal sense of duty begs inspection. Ultimately, A Few Good Men places us squarely in the middle of deciding whether or not personal accountability can be waived by institutional authority, or does true honor lie in the courage to question authority as opposed to blindly following it?

The world of A Few Good Men is built on strict adherence to hierarchy within a given system, namely the United States Marine Corps and United States Navy. Inside this system there is a zero tolerance policy for those who do not follow orders without hesitation. On the surface, this might seem like a logical method of operation being in such close proximity to enemy soldiers who train incessantly with the expressed purpose to kill Americans. Based on the amount of danger the marines in this story live in, unswerving loyalty and instant response seems to make a great deal of sense. There is, however, an inherent downside to this mindset: It breeds moral and ethical complacency. Why would a soldier need to think on their own? They have been trained that this is their duty to accept orders without any form of consideration for whether or not the order is legal or ethical. Colonel Jessup reinforces these ideals by saying that this mindset is necessary for the protection of the nation and that absolute obedience is a requirement to that end. But a price is paid for the ideals he supports. The flaw in this logic is that people commit terrible acts when their conscience is deactivated by the conditioning of leadership.

Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee has a distinct character arc. It exemplifies the decision making process between compliance and moral awakening. In the early parts of the movie we see the ultimate representation of the easy route -- he cuts deals, avoids conflict and the courtroom all while treating court cases as procedural tasks instead of moral exercises of right and wrong. His methodology is to create scenarios where the amount of work to see justice done for an opposing lawyer becomes so outrageous that they reduce the consequences in a plea bargain and therefore avoid the courtroom.

Kaffee has a very limited idea about the mindset one has to have to be a marine. The high-minded duty and the acceptance of orders with little or no real consideration simply does not compute in his comparatively pampered little world. His self-awareness increases as the movie progresses, wondering why such an inexperienced lawyer with a history of plea bargaining be given a murder trial. But as the trial progresses, Kaffee begins to see the deeper implications of the “Code Red.” He began to believe that there was more at stake in this case than a “set of steak knives”. His decision to put Colonel Jessup on the stand and challenge him in the courtroom could be considered a turning point for Kaffee. When Jessup shouts, “You can’t handle the truth!”, the audience witnesses the moment when institutional arrogance collides with moral truth. Jessup believes that his authority and his mission justify all actions, that the end justifies the means, but the trial exposes that belief as both dangerous and self-serving. In contrast, Kaffee’s pursuit of justice shows that true strength lies not in obeying orders, but in holding those in power accountable for their actions as well those under their command.

In the film's waning moments, A Few Good Men makes abundantly clear that moral responsibility cannot be transferred up the chain of command. Simply because you were given orders, does not mean you do not bear responsibility for the outcome of carrying out those orders. In a bleak reminder that although Dawson and Downey were not found guilty of murder -- they were convicted of “conduct unbecoming of a Marine” -- we all bear the weight of our choices. Dawson explained the verdict to Downey saying, “We were supposed to fight for people who couldn’t fight for themselves. We were supposed to fight for Willy.” This reflection demonstrates his understanding that while the system may demand obedience, morality and ethics requires courage.

Loyalty and morality are not the same thing. There are places such as the military where obedience can be a facade for injustice. Being loyal to a commanding officer does not mean you cannot show courage standing against wrongdoing -- even when it comes from above. The excuse “just following orders” holds no validity when considering that personal accountability is not optional. Personal accountability is the foundation of true honor. A Few Good Men shows us that having integrity is not about doing what we are told -- it is about always doing what is right.